If you have something for us that we can post about dealing with transgenerational trauma (a photo, a thought, a short story, a link), please send it to us under “Contact”! We look forward to receiving submissions with a short note on why you think it would fit in here! Thank you!

PROJECT

Bodies have a history and a memory. They remember the history of violence, racism and antisemitism, even if our consciousness may have forgotten or repressed these experiences. Thus, the body can be understood as a historical archive that bears witness to past injuries and the present forms of injustice derived from them.

But how does the body remember these experiences of extreme violence that shape and historically form it? And how is the memory and language of the body to be deciphered? To learn to interpret somatic memory in the social sciences, we must turn to medicine and neuroscience. Research on the transgenerational epigenetic effects of trauma provides nuanced accounts of how historical violence translates into somatic signatures and how traumatic events can alter genetic transcription mechanisms across generations.

The research project “Somatic Memory of Historical Violence” (Trans-somatic) examines how traumatic experiences of antisemitism and racism leave physical traces that can be passed down over generations. Biomedical studies – for example, on the consequences of the Holocaust, genocidal violence, or daily racist discrimination – are critically reflected from the perspective of history and the social sciences. To what extent does medical and neuroscientific research hold new perspectives regarding the body’s history of violence? Do the mutual references between different groups of victims, especially in the field of the epigenetics of trauma, open up a perspective of “multidirectional somatic memory” instead of promoting a mode of competition? At the same time, to what extent does the medical perspective on violence, racism and antisemitism also reproduce essentialist and biological modes of thinking?

This research project reads the epigenetics of trauma as a history of the body and uses biomedical studies for new concepts and methods to explore the memory of the body in the social sciences. Conversely, it analyzes how medical research informs social and political debates about the relationship between racism and antisemitism, the Holocaust, genocide, and colonialism. Finally, the project examines potential opportunities and pitfalls regarding the use of genetic knowledge to study racism and antisemitism.

To this end, the project is structured into four analytical perspectives and their subsequent lines of inquiry: 1) a history of science tackling the transitions between eugenics, genetics, and epigenetics; 2) a historical discourse analysis of connections between transgenerational studies on antisemitism and other forms of racism; 3) a medical anthropological approach that differentiates and interprets epigenetic mechanisms as somatic memory; and 4) a theory-political as well as self-critical reflection on physiological approaches to race, racism, and antisemitism.

The project encompasses a historical time frame from contemporary history to the present which combines knowledge primarily from Germany, the USA, and Israel. From an interdisciplinary perspective, the project moves between medical history and anthropology, medicine and epigenetics, Holocaust and trauma research, antisemitism and racism research, and critical race theory.

DIMENSIONS

The project is structured in four dimentions whereas each is framed in a particular disciplinary line of inquiry and an according methodology. It combines perspectives of a history of science, discourse history, medical anthropology, and political theory to unravel the somatic memory of historical violence.

(1) History of science

The first line of inquiry is a history of science, investigating the continuities and shifts from eugenics to genetics and epigenetics.

In the 19th and 20th century, eugenics was a transnational field of research with numerous ties between Germany, the USA, Great Britain, and other countries (12). The term “epigenetics” was introduced into modern biology by U.S. researchers in 1942 to describe developmental processes between genotype and phenotype and to illustrate the influence of environmental factors on genetics and heredity (13). On the one hand, US-advocates of epigenetics positioned their theory against the deterministic perception of eugenics. On the other hand, eugenicists did not base their theory on hereditary assumptions alone, but took the environment and milieu into account.

Thus, epigenetics was placed within the same discourse and conceptual framework of heredity and environment, and eugenicists used it to differentiate and legitimize their claims. Especially for the German speaking region, which is at the center of this first dimension, these entanglements and their influence on genetic concepts and methods have hardly been investigated (14). It is therefore examined to what extent epigenetic approaches reproduce eugenic concepts and assumptions of genetically definable social groups, of their developmental stages and their (social) pathologies.

The focus lies on the historical continuities of genetic and epigenetic research (e.g. the use of empirical data) as well as on the methods and basic assumptions after 1945. To what extent did research on race and eugenics prefigure perspectives in epigenetics?

This historical investigation is based on archival material and literature.

(2) Discourse History

The second historical line of inquiry investigates the discourse history of transgenerational trauma research, its protagonists, and reinterpretations.

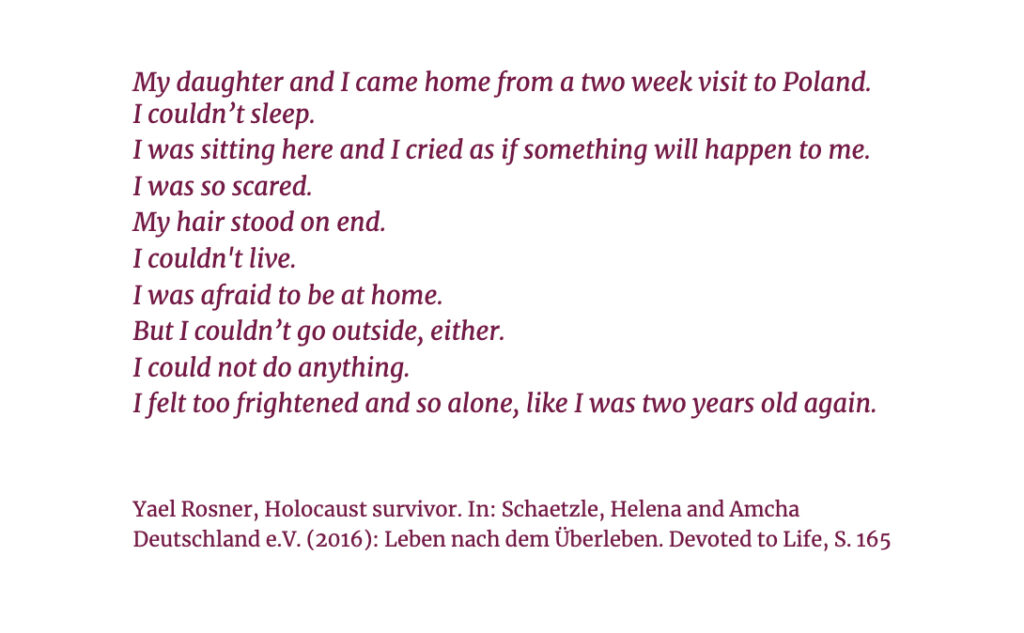

In the 1980s and 1990s, first major studies were researching the epigenetic effects of trauma in Holocaust survivors and their children (16). Studies showed that epigenetic changes caused by parental trauma were transmitted to children of Holocaust survivors, leading to an altered stress response – which could be expressed as PTSD or, on the contrary, resilience. This research was adopted to address the effects of trauma in survivors of genocide (17), Black Americans (18), and European Sinti and Roma (19). Further studies suggest that the historical experiences of the slave trade and colonialism are also transgenerationally transmitted (20).

This second dimension examines which connections between different traumatic instances and the affected groups are in fact drawn in public, academic and political discourse. What, then, are the implications of epigenetic studies for historical debates on the relationship between antisemitism and racism, and for a modern history of violence? It is reconstructed how assumptions about Jewish Holocaust survivors and their children are adopted by other groups and transferred to them. If the Holocaust is unprecedented in Yehuda Bauer’s sense, can it yet become the precedent to address other forms of collective violence, and to enable their articulation? Furthermore, how are other references to epigenetic research on the experiences of war, flight and migration, hunger, persecution, child abuse, and sexualized violence used (22)?

Methodologically, elements of historical discourse analysis are used to address the genealogy of epigenetic trauma research.

(3) Medical-anthropological

The third line of inquiry takes a medical anthropological approach.

Epigenetics is tackling a cellular memory of sociohistorical factors (26). Epigenetics, unlike genetics, is not concerned with the DNA sequence itself, but with different factors in its transcription process. Different epigenetic signatures emerge depending on the form of violence, age when trauma occurred, and gender. All these factors also influence transgenerational transmission (28). While epigenetic signatures cannot be distinguished (yet) by specific instances of historical trauma – such as the Holocaust compared to the genocide in Rwanda – a differentiation according to different forms of violence is indeed possible. For example, acute violent events can result in epigenetic signatures distinguishable from those following chronic experiences of violence (29). Furthermore, the social communicability in society, family or therapy plays a central role – up to the development of resilience instead of a “dysfunctional“ stress response.

In this third dimension, the findings of epigenetic research are used to develop reflected concepts and methods capturing somatic memory and the embodiment of antisemitic violence for the history and anthropology of the body. This part of the project is thus concerned with the actual epigenetic processes through which violence and trauma are inscribed in the body. It offers a systematic approach to the specific epigenetic signatures, accentuating which contextual differences do, and which do not show on a molecular level.

Methodologically, elements of Actor-Network Theory are used to analyze altered epigenetic transcription processes in relation to their empirical observation in the laboratory.

4) Political Theory

The fourth and last line of inquiry is concerned with a conceptual and theory-political evaluation of material and medical perspectives on antisemitism, the Shoah, and racism.

Whereas Anglo-American approaches to race, racism, and antisemitism have long turned to material perspectives (30), German scholarship on antisemitism has remained largely reluctant to the proposed “material turn”. One reason may be the valid suspicion of biological approaches to antisemitism and social problems more broadly, which can seem reminiscent of the history of National Socialism . However, this project takes the stance that there is much to gain from physiological perspectives on trauma and antisemitism. This dimension therefore aims to problematize the material approaches against the backdrop of German history and context and, more specifically, aims to implement the awareness and lessons of German history to material, medical and physiological approaches to antisemitism and Shoah, as well as to the physiology of violence more broadly.

This part of the project also serves the critical evaluation of the preceding three dimensions. If antisemitic and racist violence create genetically relevant changes, doesn’t this imply the problematic assumption that those Jewish, Black or Roma people targeted by it are genetically specific and differentiated groups? Furthermore, if these epigenetic changes more often lead to dysfunctional stress mechanisms, doesn’t this concur with classical racialist ideas about biological inferiority?

What are the potentials, and which are the problems and pitfalls of using biomedical data for the study of antisemitism and Holocaust trauma? Which concepts are loaded with racial knowledge and how can we conceptualize a context-sensitive language for the physiology of collective violence? Are there lessons to be learned from German history for transnational discourses on the “physiology of racist oppression” and the controversy about the concept of race (and “Rasse”) in Germany? (32)